Three Cheers for Micro Four Thirds

Why I still love this camera system after 10 years and can’t imagine switching to another format

In early 2013, I decided that I was going to leave my home in the US to get an ESL certification in Budapest, Hungary. I bought myself a one-way ticket and had no idea when I’d move back home. (I still don’t - it’ll be ten years in February.) At the same time, I made another momentous decision: selling off all of my Canon full frame DSLR gear in favor of a relatively new and very different system, mirrorless micro four thirds (MFT, M43, M4/3…). Anyone who has been into photography for a while will know that switching formats is a pretty rare thing; people tend to get deeply invested (both financially and emotionally) in one brand and often make it a part of their identity. (Canon vs. Nikon is like Ford vs. Chevy in the camera world.)

Switching from a full frame DSLR to a mirrorless MFT camera in 2013 was like trading a Camaro for a Corolla - not at all self-explanatory. It was, in fact, entirely conditioned by my plan to move abroad. As great as Canon’s EOS cameras and lenses are (and they are great, to be sure), they’re also bulky and expensive. So, while I was selling most of my other worldly possessions in advance of the move, the Canon stuff all had to go too, to be replaced with something more appropriate for a cash-strapped traveler.

Enter the mirrorless MFT system. Launched in 2008 as a joint venture by Panasonic and Olympus, MFT was a new interchangeable lens camera format based on the four thirds DSLR system, developed by Olympus and Kodak in the early 2000’s. The M (micro) in MFT refers to the camera bodies and lenses being smaller than those of four thirds DSLRs due to the lack of a mirror box assembly - the sensor specification is the same. Now, ten years thence, mirrorless cameras are the rule rather than the exception, with big players like Sony, Canon, and Nikon all fully invested in new mirrorless bodies and dedicated lenses. (Canon hasn’t released a new DSLR model since January, 2020.) The MFT system, however, has remained a relatively niche choice, especially for professionals.

I think that’s a mistake, and I’ll explain why.

Above: These photos were all taken with the Olympus EM-5, the first MFT camera I bought.

First of all, it’s important to point out that the reason that multiple manufacturers and systems exist, even within the mirrorless camera market itself, is that there is no best system for everyone. Every choice involves tradeoffs among things like cost, image quality, portability, features, available lenses, et cetera. The reason that I continue to use MFT cameras is that, for me at least, the benefits of this system vastly outweigh the drawbacks, which I’ll get into below.

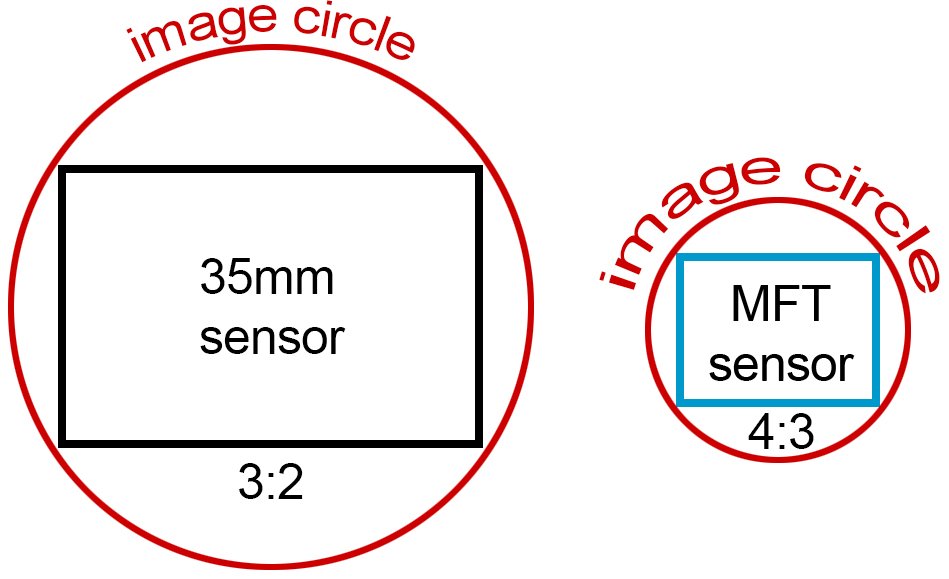

The only important difference between MFT cameras and all other mirrorless digital interchangeable lens cameras is the size of the imaging sensor. The “full frame” sensors on professional-grade digital cameras are about the same size as a frame of 35mm film. (Digital cameras started out as digitized versions of 35mm film cameras, so we still talk about sensor size with film size as the “default” reference.) Some digital cameras have sensors larger than full frame (lumped together as “medium format”), but until very recently these were extremely expensive and not widely used. Many digital cameras have sensors smaller than full frame. MFT cameras use the smallest sensor size currently available for interchangeable lens cameras. As you can see in the image above, the four thirds sensor is about a quarter of the size of a full frame sensor.

This difference in sensor size allows both MFT cameras and lenses to be considerably smaller, lighter, and cheaper than their larger format equivalents. As you can see in the comparison above, the image circle of a lens for an MFT camera is a quarter of the size of that of a full frame lens. This has massive implications for the size, weight, and cost of MFT lenses compared to their full frame equivalents. I’ll give some specific examples later to illustrate just how much this actually matters in the real world. This, in short, is why I love MFT - everything is smaller, lighter, and cheaper.

Ok, so, what’s the catch?

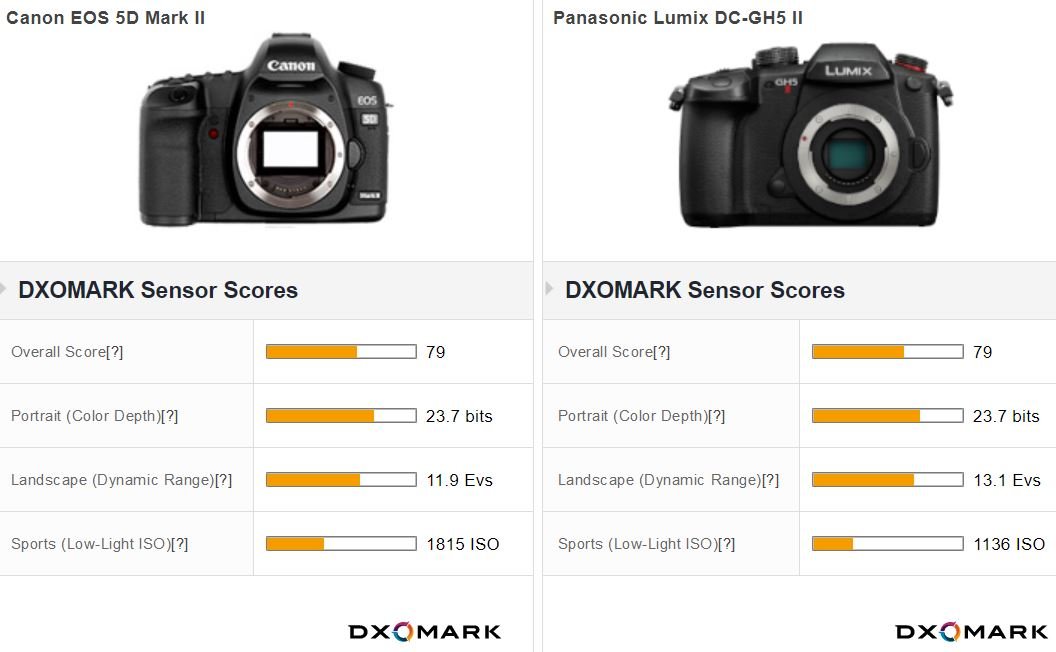

Smaller sensors suffer in comparison with their larger counterparts in two main ways: resolution and low-light performance. These two things are important in determining overall image quality, so it’s completely fair to say that, ceteris paribus, MFT cameras have lower ultimate image quality than larger format cameras. This is a consequence of how digital sensors work and is not really up for debate. The amount of difference will depend on exactly which two camera models one compares, but here’s one example to illustrate the point. Panasonic currently produces camera bodies with four thirds and full frame sensors, so here’s a comparison from DXO Labs (an independent company that tests and reviews digital sensors) between two of Panasonic’s cameras released around the same time:

As you can see, the smaller sensor (on the right) is inferior to the full frame sensor in every metric, especially in low-light ISO performance. This is what can be expected at the moment no matter which MFT and full frame bodies are compared - the color depth and dynamic range will be a little bit worse, and the low-light ISO performance will be significantly worse for the MFT camera.

That’s it. That’s the disadvantage.*

The question is, how noticeable is this gap in ultimate image quality in the real world in most situations?

In my experience, the answer is not particularly noticeable at all. That’s because, although four thirds sensors are inferior to full frame sensors, they’re still extremely good. It’s sort of like owning a car with a top speed of 220 mph vs. 155 mph. Yes, technically one is much faster than the other, but both of them are fast enough for all practical driving situations. The advantage of the 220 mph car is hypothetical rather than practical. Photographers love to get into specification pissing contests (see my above comment on Canon vs. Nikon) over which camera has the better DXO score, not realizing that the cameras that they’re arguing about are all beyond good enough for most photographers most of the time. I’m going to argue here (perhaps controversially) that the low-light ISO performance between the two Panasonic cameras above, for example, even though it is vast, is in practical terms negligible for most photographers most of the time. Why is this?

Well, for starters, low-light ISO performance has been steadily improving on MFT cameras. It’s been improving on full frame cameras too, but the rising tide of technological progress raises all digital boats. Look at that same Panasonic MFT camera compared to the Canon 5D mark II, the last full frame camera I owned:

The overall image quality scores are the same. Yes, granted, the 5DII still has better low-light ISO performance, and that camera was released in 2008. Why am I cheering for an MFT camera that is only as good as full frame cameras were 15 years ago? Because there’s nothing wrong with the images that the 5DII makes - it’s an amazing camera. Now imagine taking that image quality and packaging it within a camera system that has 15 years of other technological advancements and is a fraction of the size, weight, and cost of full frame cameras. That’s basically what MFT cameras offer these days.

Another reason that the gap in DXO scores doesn’t really matter is that MFT camera manufacturers know that this gap in image quality exists and compensate for it with innovative technological solutions. (To keep the car analogies going, consider two competing ways to make lots of power - massive displacement and small displacement + forced induction. MFT is a 1.6L turbo 4-cyl, full frame a 6.2L V8.) Olympus in particular has been pioneering image stabilization on the sensor itself in order to reduce the need for increasing the ISO sensitivity. Olympus has also produced image-stabilized lenses which, when paired with Olympus MFT bodies, can offer 6+ stops of compensation for camera shake. This means that it’s (theoretically) possible to capture a 10-second hand-held exposure at wide focal lengths, which is bonkers crazy-pants. If you’re shooting moving subjects and can’t use a long exposure to avoid high-ISO levels, Olympus makes several (still surprisingly small!) prime lenses with a maximum aperture of f/1.2 to keep those shutter speeds up in dark conditions. Again, this doesn’t mean that it isn’t easier to get low-light performance with full frame cameras - it definitely still is - but it’s also possible to get the results you want in low light with an MFT camera.

So, with the major drawback out of the way, let’s talk advantages of MFT cameras.

#1 - Size, weight, cost.

This is really what sold me (literally) on jumping ship to MFT and keeps me there year after year. You can get the same quality equipment (or better) for less money and with less size and less weight. I’ll provide some examples here that I think illustrate this perfectly (and frankly make me wonder why so many people continue to insist that they need a full frame camera).

[Note for these comparisons: I’m using pxlmag for the images of bodies/lenses and B&H for MSRP and specifications. I’m trying my best to provide reasonable comparisons while acknowledging that there isn’t always a perfect one-to-one equivalent available between MFT and full frame offerings, and there are always multiple different camera bodies and lenses to choose from for each. I can’t compare everything.]

Example 1: Entry-level body + entry-level zoom lens

Let’s say you’re just starting out with photography and don’t need professional-level quality. You also just want one lens that will do it all. Here are two comparable (in terms of focal lengths covered) solutions with MFT and full-frame systems.

Olympus E-M10 mkIV + Panasonic 14-140mm f/3.5-5.6 II vs. Canon EOS RP + Canon 24-240mm f/4-6.3

| Body and Lens | Total Cost | Total Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Olympus E-M10 mark IV + Panasonic 14-140mm | $1,296 | 648 grams |

| Canon EOS RP + Canon 24-240mm | $1,898 | 1,236 grams |

Keeping in mind that the full frame camera is going to have better resolution and low-light ISO performance, let’s look at these two body + lens combinations. The Olympus/Panasonic offering is $600 cheaper and half the weight of the Canon. You can also see from the image (which is to scale) how much smaller the MFT lens in particular is. With that extra money you could buy a second lens and store it in the extra space not taken up by the huge Canon lens, which accounts for most of the size and weight disparity between these two kits.

Speaking of the lenses, let’s see how they compare. Remember that MFT cameras have a 2x crop factor compared with full frame due to the smaller sensor, so the focal lengths covered by these two lenses are 28-280mm for the Panasonic and 24-240mm for the Canon. The Canon has the edge for being slightly wider (24mm), but the Panasonic has 40mm more reach on the telephoto end. Both of these lenses have variable maximum apertures, but the Panasonic is faster at all focal lengths (f/3.5-5.6) than the Canon (f/4-6.3). The Panasonic also has a much smaller filter size (58mm vs. 72mm) and has a closer minimum focusing distance (30 cm vs. 50 cm).

Given that both of these cameras will produce great images in most photographic situations, is the full frame really worth an extra $600, much larger dimensions, and double the weight?

Example 2: Professional body + standard fast zoom

Let’s say you’re a professional looking to pick up the best available body and want a standard 24-70mm f/2.8 zoom with weather sealing. Here’s what some MFT and full frame choices look like.

Panasonic G9 II (G9 pictured) + OM System 12-40mm f/2.8 vs. Sony α9II + Sony FE 24-70mm f/2.8 II

| Body and Lens | Total Cost | Total Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Panasonic G9 II + OM System 12-40mm | $2,896 | 1,040 grams |

| Sony α9 II + Sony FE 24-70mm f/2.8 II | $6,796 | 1,373 grams |

The size and weight of these two kits are much more similar than in the previous example, although the MFT body and lens combo is still smaller and 300 grams lighter. These two cameras are a closer match than one often finds between MFT and full frame. In this case, the Panasonic actually offers a higher resolution sensor (25.2 MP) than the Sony (24.2 MP) while also featuring a 100 MP high resolution shooting mode that the Sony lacks entirely. While the Sony will have much better low-light ISO performance, both of these cameras offer professionals top-notch specs for both stills and video.

The alpha, though, with this FE lens, costs 2.3 times more than the Panasonic and OM System pairing, or $3,900 more in absolute terms. Again, is the bigger sensor worth $3,900 and more weight and bulk?

Example 3: A complete zoom kit

Let’s eliminate the variable of the camera body and just concentrate on building a professional-grade kit of three zoom lenses: a wide angle, a standard, and a telephoto zoom. This is an easy comparison to make, because more-or-less equivalent lenses exist for both systems for easy comparison. Here are the current professional offerings from OM System (MFT), and Sony and Canon (full frame).

Olympus/OM System trio: 7-14 f/2.8 (not correctly pictured), 12-40 f/2.8, 40-150 f/2.8.

Sony E-mount trio: FE 16-35 f/2.8 GM II, FE 24-70 f/2.8 GM II, FE 70-200 f/2.8 GM OSS II

Canon RF trio: 15-35 f/2.8 IS L, 24-70 f/2.8 IS L, 70-200 f/2.8 IS L

All three of these lens kits are quite evenly matched in terms of their focal lengths, constant f/2.8 maximum apertures, and professional quality weather sealing. So how do they compare in terms of price and weight?

| Lens Kit | Total Cost | Total Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Olympus/OM System | $3,897 | 1,676 grams |

| Sony E-Mount | $7,394 | 2,287 grams |

| Canon RF | $7,477 | 2,810 grams |

If these numbers don’t underscore the massive advantage that shooting MFT offers, I don’t know that anything will. Half the cost and much less size/weight to cover the same focal lengths at the same maximum aperture compared with full frame equivalents. I say equivalents, but actually I bent the rules in order to be kind to Canon and Sony. In full frame terms, the Olympus 40-150mm f/2.8 telephoto included above is equivalent to a 100-300mm f/2.8 full frame lens. Canon does make an RF 100-300mm f/2.8 lens. It costs $9,499. The Olympus zoom, which I’ve owned for years, covers the same focal lengths at the same maximum aperture, is dust and weather sealed, and costs 15% of the price of the Canon. It also weighs 1.8 kilograms less. Lawl.

If you were to add the cost of a professional camera body with these Sony or Canon kits, you’d be spending 11 to 12 thousand dollars, or, you know, the price of a relatively new used car. This is only insane because of the existence of much cheaper but still extremely high-quality alternatives like MFT (not to mention APS-C offerings from Canon, Sony, Fuji…).

#2 MFT-Exclusive Lenses and Technologies

The benefits of MFT go beyond the cost and weight savings over full frame cameras. The smaller format means that lenses that would be impractical or impossible to make for full frame cameras are readily available for MFT cameras. I already mentioned the Olympus 40-150mm f/2.8 above, but Panasonic makes a 200mm f/4 (400mm in full frame terms) prime and Olympus a 300mm f/4 (600mm equivalent) prime, each for under $3,000. If you really want to get crazy, Olympus makes a 150-400 f/4.5 (300mm-800mm equivalent) zoom. It’s quite expensive at $7,499, but nothing even remotely similar exists for full frame cameras.

But MFT doesn’t just dominate in telephoto lenses. Fast primes and zooms exist as well, again with no full frame equivalents. My favorite Olympus lens, for example, is the 12-100mm f/4, which has no full frame counterpart. This fast super-zoom (24-200mm equivalent) isn’t big or heavy and is the ultimate lens to take if you’ve only got room in the bag for one. Panasonic makes two zoom lenses (10-25mm and 25-50mm) that have a constant maximum aperture of f/1.7. Canon only has one RF zoom that’s faster than f/2.8, and it costs $3,100 and weighs a kilogram and a half. Sony doesn’t currently make any. Olympus makes a trio of f/1.2 prime lenses at 17, 25, and 45mm (34, 50, and 90mm equivalents), while Canon only has two f/1.2 RF lenses (the 50 and 85mm, both expensive and heavy) and Sony only makes one (50mm). If f/1.2 isn’t fast enough for you, there are several manufacturers making manual focus primes for MFT with maximum apertures faster than f/1.0.

Then there’s the technology side. I mentioned earlier that MFT camera manufacturers know they’re at a disadvantage when it comes to ultimate image quality, so they need to compensate with clever engineering. The OM System OM-1 camera is a great example of this. It has five different computational multi-shot modes, all of which take multiple images and then process them into a single shot in order to produce results that would be otherwise impossible, much like current cell phone camera software does. It can capture a 50 or 80 megapixel high resolution image, for example, by taking multiple offset images and quickly compositing them together. This works extremely well and is a feature I’d never want to be without now that I have it. It can also use multiple short exposures to simulate the use of a neutral density filter. This means it’s possible to get motion blur in a single hand-held image in broad daylight. Without this feature, you’d need a set of ND filters and a tripod. It also has a live composite mode, which layers successive long exposures but only records new light information, like star trails. It will also do focus stacking automatically in-camera for macro shots. For sports or wildlife photography, it has a feature called Pro Capture, which starts recording images at up to 50fps (with continuous autofocus) when you half-press the shutter. This makes it much easier to get the perfect shot from a fast-moving subject. (The five images above were all captured using one of these computational modes.) I think the current state of MFT technology is summed up well by this quote from dpreview.com’s review of the OM-1 (emphasis mine):

The OM-1 excels in situations such as wildlife shooting, where its power and compact telephoto lenses mean it's able to offer an unmatched combination, but it can also be a pretty capable sports camera or a general, everyday photographers' camera expected to shoot a bit of everything. So, while it can't generally match a comparably priced full-frame camera for image quality, but there's nothing else that offers this level of all-round capability (shooting speed, AF performance, IS performance, weather sealing) in such a small package.

I don’t have much to add to that from my ten years of experience shooting with MFT cameras. When I travel, which I do a lot, I can carry multiple camera bodies and lenses with me easily and be confident that, no matter where I am, I have the necessary gear with me to get the shot, every time. That’s not easy with full frame cameras (unless money is no object and you’re a body builder).

In sum

I said in the preamble that there is no best camera system for everyone, and that’s important to reiterate here at the end of my encomium of MFT cameras. There are professionals out there, for example, who are making fine art prints or doing highly specialized photography that demands certain specs and capabilities. MFT cameras may not be for them. Then, though, there’s everybody else - the hobbyists, enthusiasts, and even part-time professionals who take pictures for creative and recreational purposes. People like me, and probably you, reader. People who would be perfectly happy shooting MFT cameras, if only they saw past the hype of full frame (a lot of it is hype) and looked without bias at what smaller sensor cameras have to offer. There are way too many people out there - I know because I used to be one - who have an interchangeable lens camera but don’t use it very often, partly because it’s expensive, but mostly because it’s too bulky and heavy to take out anywhere. On my recent trip to Fiji (for which my OM-1 and 12-100mm f/4 lens was more than sufficient), a colleague of mine said at dinner one night that she used to have an expensive DSLR but got rid of it because it was too much of a hassle to carry around, even on vacation when she wanted good photos. Now she just uses her phone instead.

It doesn’t have to be this way! Your choices are not a $5,000 Sony alpha or an iPhone. You can walk a middle path with smaller, cheaper, lighter gear that still produces stunning images. There is so much choice available to photographers of every aspiration that everyone should be able to find the right fit. I think, though, that persistent misconceptions about image quality mislead many photographers into bad decisions.

So, if you’ve got a giant camera that you rarely ever use; if you only have one lens for your interchangeable lens camera because you can’t justify the additional cost; if all you do with your photos is share them on social media and make prints for your house, you should probably be shooting micro four thirds.

Just my opinion. Three cheers for MFT!

*I can anticipate some push-back on this point, because there are other inherent differences between four thirds and full frame sensors. For example, people will be quick to point out (correctly) that the 2x crop factor on four thirds sensors applies to depth-of-field (i.e. bokeh) as well. While this could be a problem for, say, professional portrait photographers, there are other situations in which having more depth-of-field at the same aperture is a positive thing. I would only classify something as a disadvantage if it really is worse in all scenarios, as lower overall image quality is.